L.A. River Runs Through It

By ARNIE COOPER

Pasadena, Calif.

In Paris it’s the Seine. In New York it’s the Hudson. And here in the Los Angeles Basin it’s, well, a concrete channel unceremoniously called the Los Angeles River.

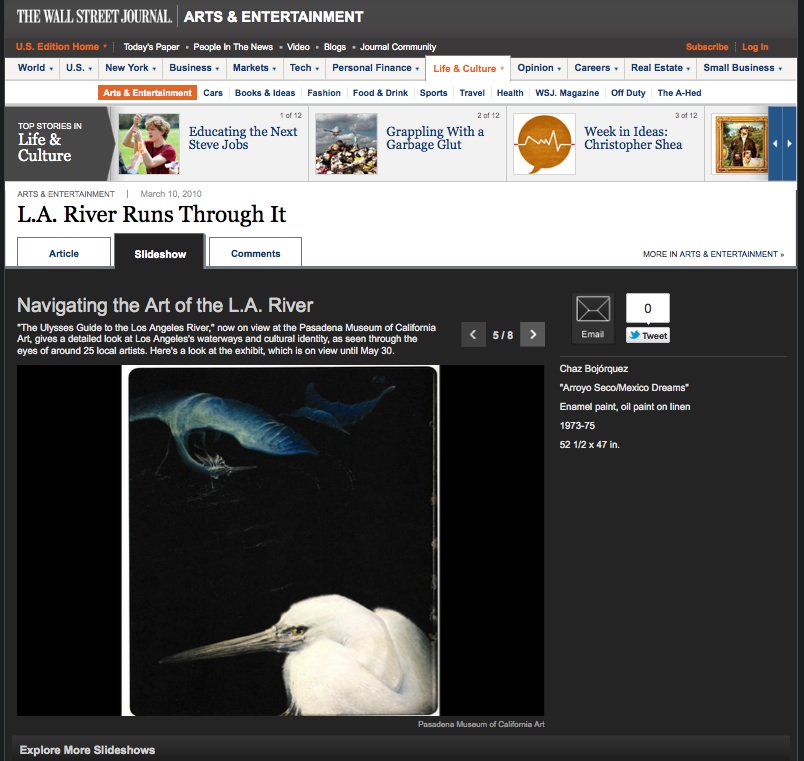

But joke all you want. The 51-mile creation of the Army Corps of Engineers may not be most Angelenos’ prime destination for a Sunday stroll—heck, it might not even be flowing—but as Charles “Chaz” Bojórquez, one of the artists in the Pasadena Museum of California Art’s current exhibition, insists: “This is our river; this is our community and our history, so it’s more than just water down a concrete gateway.”

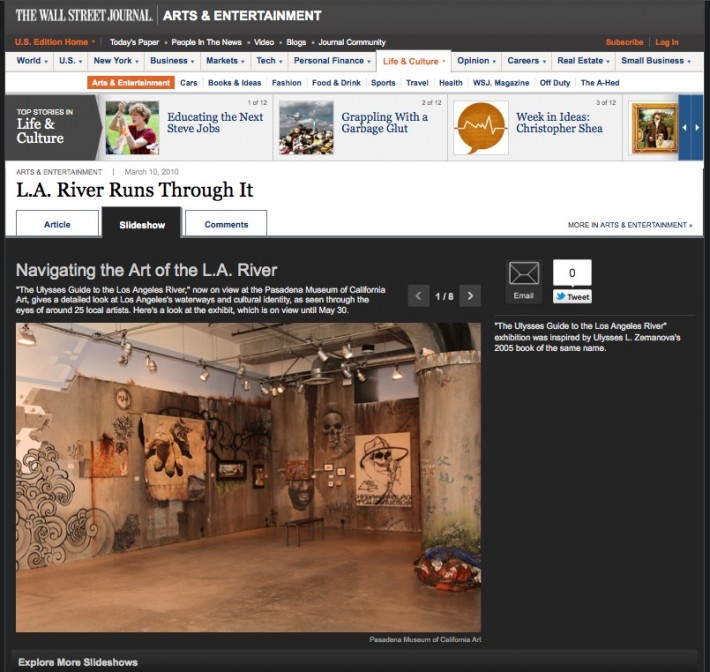

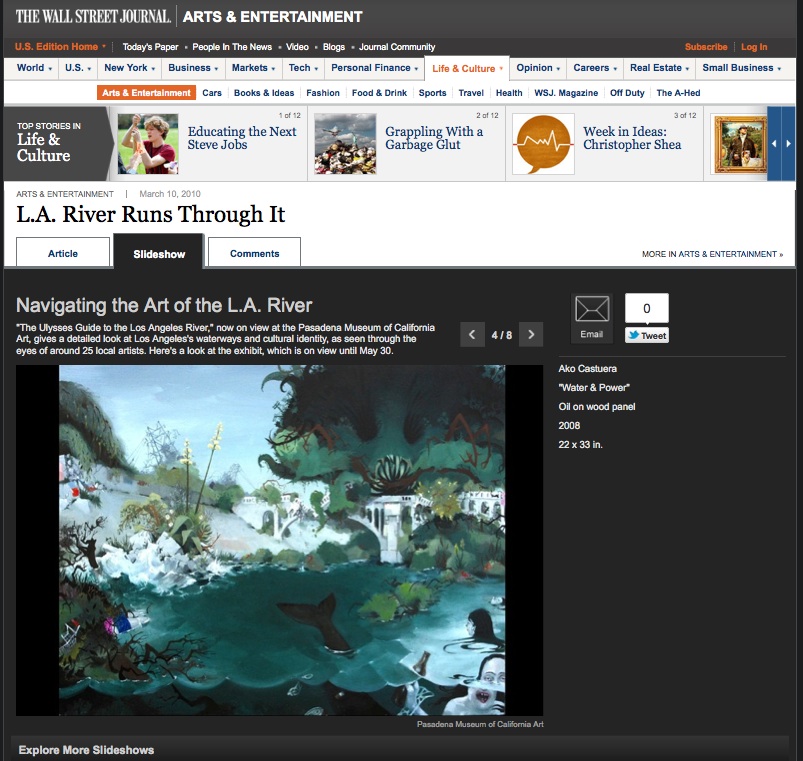

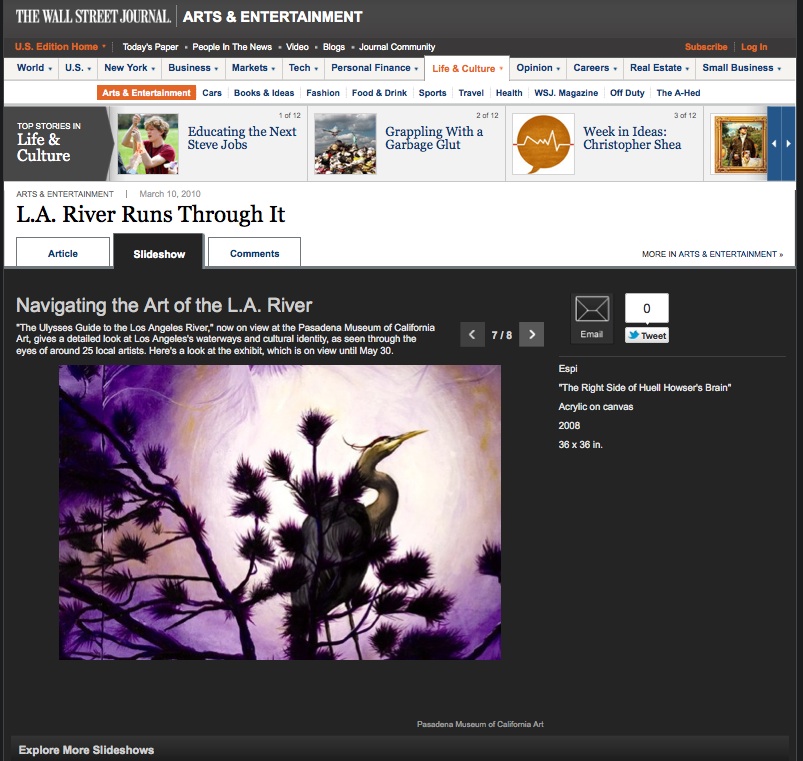

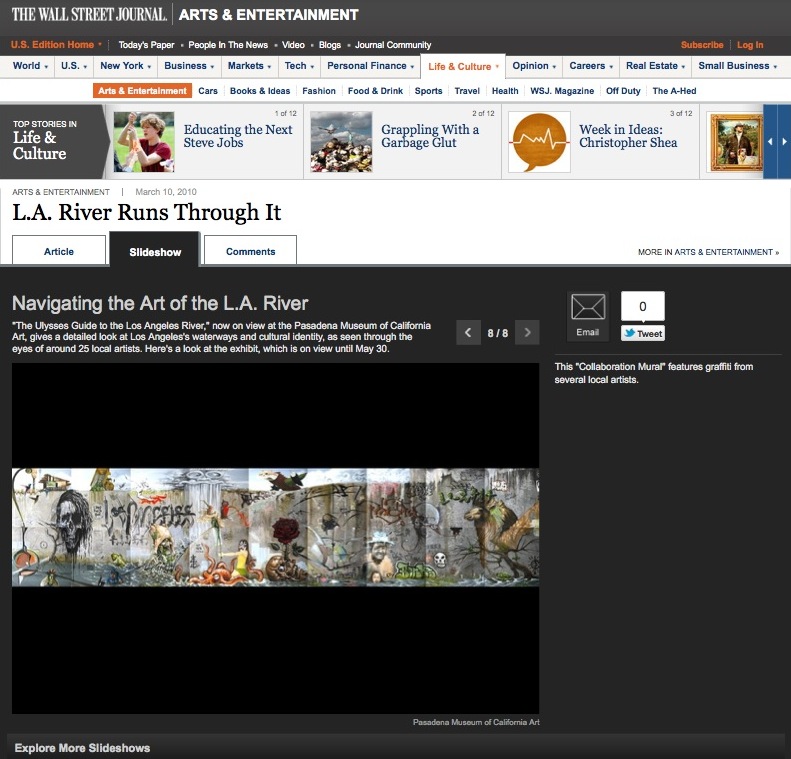

“The Ulysses Guide to the Los Angeles River,” inspired by Ulysses L. Zemanova’s 2005 book of the same name, offers visitors (whose main contact with the river is likely through their windshields) a detailed look at the waterway’s flora, fauna and cultural identity as seen through the eyes of 25 or so local artists. There’s sculpture, photography, pen and ink, watercolor, oils, mixed media and, as you’d expect, a preponderance of graffiti—some of which dates back to hobo etchings from 1914.

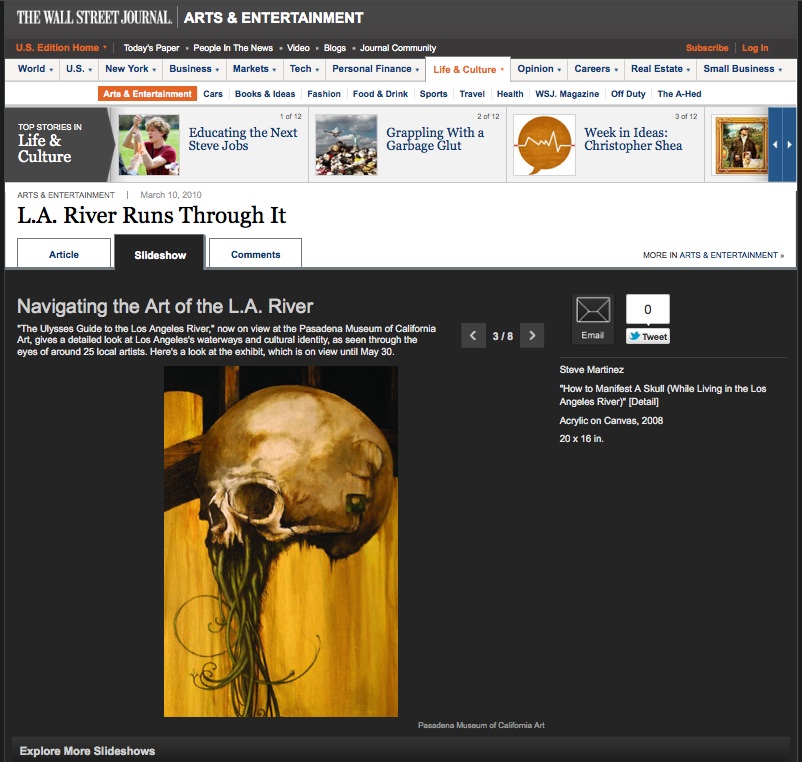

No wonder the show’s curators, Christopher Brand, Evan Skrederstu and Steve Martinez, are all graffiti artists in their 30s who’ve logged many hours in the city’s circulatory system. The same is true for 60-year-old Mr. Bojórquez.

A self-proclaimed hippie (“I was not a gang member, but my neighbors were,” he writes in the book), Mr. Bojórquez grew up in Highland Park, using the river to escape the violence and ugliness of the streets above. “The river was always a positive place to go. Surprisingly, it was beautiful down there,” Mr. Bojórquez says. “Late at night when you’re doing graffiti with the river’s sound, the freeways and with a full moon, you could look down at all the broken bottles and see a diamond-studded highway.”

No doubt, for all the insults hurled against what is frequently just a trickle of fluorescent green algae, the river—to those who actually spend time in it—is, says Mr. Skrederstu, “a weird little escape from the city. You’re still in the middle of L.A., but sometimes it gets super quiet.”

Once a free-flowing alluvial river, El Río de Nuestra Señora La Reina de Los Ángeles de Porciúncula—so named by Gaspar de Portolà during his 1769 expedition of Alta California—was originally the main nutrition and water source for the Gabrielino Indians. With its stands of oak trees, small fish and mammals, the tributary helped sustain the 50 or so villages near its banks in what’s now the San Fernando Valley and Glendale.

After the Spanish arrived, the river continued as the region’s main water supply, though its path was unpredictable. Floods in the 1800s diverted its course to its current location, running from Canoga Park due south just east of the city before spilling out into San Pedro Bay. But it was a catastrophic flood in 1938 that led to the Army Corps’ project to pave its banks with concrete. The 20-year undertaking used three million barrels of concrete, inadvertently creating the city’s largest graffiti canvas.

“The point of the show,” Mr. Brand says, “is to re-create our river experiences for someone who’s never seen it. Every time we’ve been to the river, we’d come across little things that the average person might find absolutely disgusting but to us were things of true beauty.”

Consider his bizarre but highly crafted (as yet untitled) sculpture that is intended to serve as the introduction to the show. Resembling a snail adorned with baroque flourishes, algae-covered barnacles, and a single, real-looking eye peering out from a peephole at a copy of the Ulysses Guide, the creature is both ugly and beautiful. “He’s the vessel,” Mr. Brand says, “for the viewer to get involved in what you’re about to see.”

“Involved” is the key, for the curators’ main goal is not just to re-create the river (achieved with video footage of flowing water, live plants and a soundscape of all the ambient noise) but also to inspire residents of Tinseltown to actually check it out.

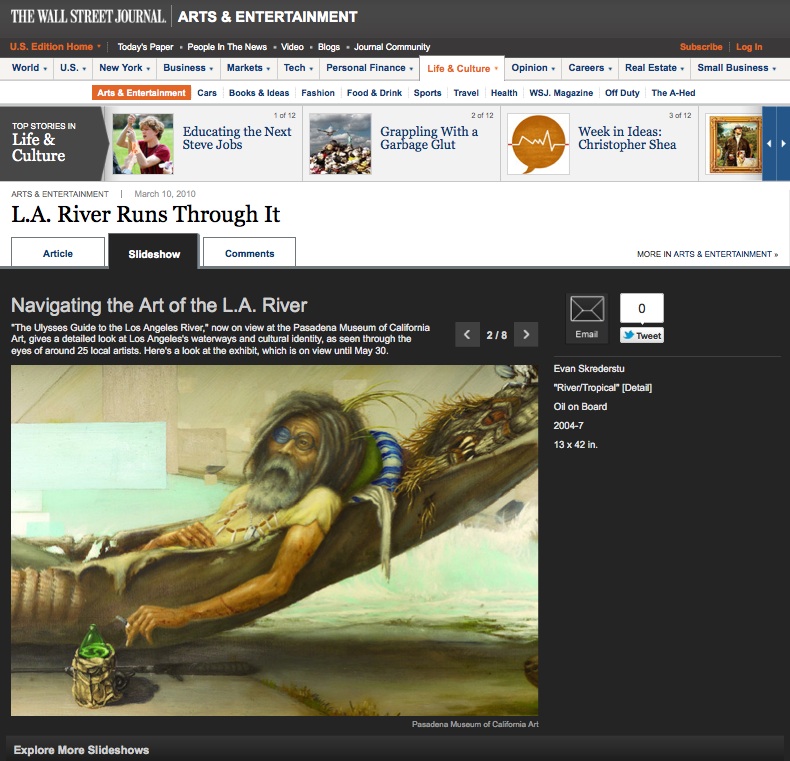

But if descending into the bowels of Los Angeles is not your thing, you’ll definitely want to gaze at “River/Tropical,” an oil-on-board painting done by Mr. Skrederstu. The 13-by-42-inch portrait/landscape contains many of the channel’s elements both real and imagined. Though the concrete banks, the aging hippie/bum surrounded by pigeons, an old transistor radio, and a cooking pot nearby are sights you might come across, not so the azure water, gorilla (or is it a mammoth?) and way in the distance a few moai—the stone carvings from Easter Island in Chile. Just to the work’s left is Messrs. Skrederstu and Martinez’s big 78-by-72-inch acrylic “Survivors of the Massacre (48),” featuring a realistic-looking, battered stuffed animal with a grasshopper sitting on its head.

Those craving something more sedate might prefer “Ol’ School Calvera Peacock,” a 2007 ink-on-paper image lyrically sketched by Jack “From-Way-Back” Rudy. For the scientist, there’s an enlarged pill bug, created by Dennis Kunkel, known for his scanning electron micrographs.

No doubt, for many of these artists, the river’s influence extends far beyond its banks. Featured in the show is an 18-foot-wide panel that has accompanied Messrs. Brand, Skrederstu and Martinez all over the world. One can’t help being drawn to its depiction of the Aztec deity, Tlaloc, which Mr. Brand says represents falling water or rain. “Tlaloc needs to be involved in this exhibit, because without that bit of water, the river and L.A. wouldn’t be here.”

So what happens if their concrete canvas gets removed or made blank once again? A nonprofit group, Friends of Los Angeles River (FoLAR), has been working since 1986 to restore the waterway to a more natural state, without much progress. But the Army Corps, thanks to $800,000 in stimulus funds, has many gallons of beige paint at the ready.

Still, like all graffiti artists accustomed to seeing their work erased, Mr. Brand is unfazed. “Everything is temporary; the river is always changing, constantly in flux,” he said. “That’s one of the points we’re making.”

Note: © The Wall Street Journal & Arnie Cooper. Read the original article here.